Brian “Bad” Phelan, New Zealander and bomb  disposal expert, likes to live dangerously. While on vacation on the French/Italian border in 2001, he helps to bring a body out of a rocky, wave-swept cove. The dead woman bears striking similarities to a young woman he met years ago, under mysterious circumstances, shortly before she disappeared in a flooded French cave. Bad is compelled to investigate.

disposal expert, likes to live dangerously. While on vacation on the French/Italian border in 2001, he helps to bring a body out of a rocky, wave-swept cove. The dead woman bears striking similarities to a young woman he met years ago, under mysterious circumstances, shortly before she disappeared in a flooded French cave. Bad is compelled to investigate.

Jesuit Father Daniel Octave is making his own investigation, into the truth behind the story of the life of the Blessed Martine Raimondi, a WWII resistance heroine and martyred nun. Bad and Daniel’s questions lead them to Eve, the beautiful widow of a celebrated French artist, and to Dawn, Eve’s twin sister, who seems to be a vampire. For, though they don’t know it, Bad and Daniel are looking for the same thing – a secret family.

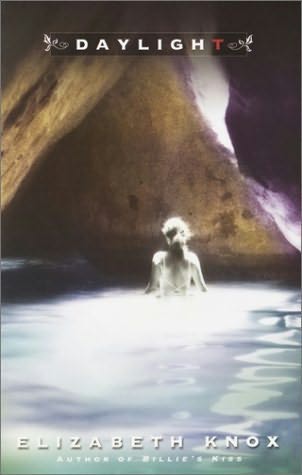

Sensuous and heavenly, Daylight combines Elizabeth Knox’s greatest gifts, her wildly imaginative storytelling and her clear eye for atmosphere and place. The vampires of Daylight are distinctly Knoxian, as intriguing and intelligently drawn as the angel in Knox’s The Vintner’s Luck. Daylight is set on the beautiful Mediterranean coast stretching from Avignon to Genoa, yet much of it takes place in a world the tourist never sees, a world of caves and secret passages. It is in this “world beneath the world” that Bad Phelan and Daniel Octave finds themselves face to face with history and myth, with phantoms whose hearts are still beating, and hungry, and able to break.

Praise for Daylight

I particularly like this intelligent review, so will quote in full.

Douglas Winter, The Washington Post, (2003)

Not another vampire novel. These days the very sight of the V-word on a book jacket prompts a shiver of dread – not of creaking coffins and the risen dead, but of one more predictable tale of bloodsucking bathos.

Introduced to Anglo-American literature by John Polidori’s skewering of Lord Byron in The Vampyre (1819) and made popular by the penny dreadful Varney the Vampire (1845-7) and Bram Stoker’s famous Dracula (1897), stories of bloodthirsty immortals have beguiled readers for centuries. But when Stephen King and Anne Rice opened the jugular of commerce with Salem’s Lot (1975) and Interview with the Vampire (1976), the culture industry gorged. Vampires became merchandise, packaged into sagas and series, hunted by demographically correct divas named Buffy and Anita Blake, wrought by a legion of lesser hands into cliché and caricature.

At first glance, then, it’s surprising to find Elizabeth Knox, a gifted New Zealander whose complex prose has summoned comparisons to Jane Austen and Charlotte Bronte, apparently slumming among the gravestones. Yet Knox, who danced with angels in The Vintner’s Luck (1998) and fractured time in the daunting Black Oxen (2000), plainly loves a challenge; and Daylight confronts a worthy one: the redemption of a tarnished icon.

Brian “Bad” Phelan, Daylight‘s protagonist, is an Auckland policeman who has been wounded by a terrorist bomb. While seeking escape via a vacation along the French-Italian border, he encounters “a series of spurious connections – indecent, unreasonable connections.” It begins in the Mediterranean off Riomaggiore, where the corpse of a woman is spotted floating in the waves at the mouth of a sea cave. Her strangely mottled hair matches that of a woman Phelan had seen die in a caving accident a decade earlier. Her face is also familiar, reminding him of the image of a woman on a poster – the last thing he had seen before the bomb went off. An experienced diver and caver, he volunteers to retrieve the corpse. He hopes that the act will help him get over his brush with death, which “had filled his soul with gloom, a shrapnel of small shadows.” But the shadows, and his wounds, only deepen.

The dead woman is Martine Dardo, namesake of the Blessed Martine Raimondi of Dardo, a martyred nun who is being considered for sainthood. The two women are one and the same, of course; but nothing is so simple in the wonder-worlds of Elizabeth Knox. Phelan is drawn into a mystery involving a startling trinity: Martine, her friend Eve Moskelute, and Eve’s twin, Dawn, whose curious manner and parti-colored hair suggest her connection to a seductive netherworld full of darkness and danger. He also meets the twins’ powerful protector, Lou Ila, an enigmatic figure with a thirst for blood and an aversion to sunlight. Phelan’s investigation crosses paths with the inquiries of Father Daniel Octave, a Jesuit priest who stumbles upon unruly facts while researching miracles attributed to the nun, and the machinations of the novel’s Ugly American, a vengeful vampire named Tom Hilxen.

These lives crash and churn like the waves beneath Riomaggiore as the plot leaps continents and decades, spiraling back to 18th-century dilettante Guy de Chambord, whose lurid novel Lumiere du Jour – yes, Daylight – reveals the cause of Lou Ila’s transformation. The explanation of the Venerable Martine’s miracles will inevitably test Father Octave’s faith and bring Ila into the light; at the same time Phelan’s “spurious connections” will prompt him to reconsider his belief in happenstance.

Knox avoids the familiar terrain prowled by this generation’s horror mavens in pursuit of a landscape of illusion. In celebrating Wilkie Collins’ The Woman in White (1860), which brought horror home from the distant castles and abbeys of Old Europe, Henry James challenged the relevance of the Gothic Romance made famous by Ann Ward Radcliffe and transfigured by Jane Austen in her satiric surrender to populist horror, Northanger Abbey(1818). What are the Appenines to us, James asked, or we to the Appenines?

Daylight is Elizabeth Knox’s riposte, urging that the Appenines, like Transylvania, exist beyond geography in a realm of the imagination, a vital dreamscape where the past survives, stripped of the dubious veneer of civilization. Their fanged inhabitants, whether named Dracula or Lestat or Ila – unleash the secret history that has been bleached of grime and tears and blood by the bright light of progress, and offer guilt-free fantasies of intellect and flesh. Cerebral, cultured and noble (if not aristocratic), these avatars of impossible romance and immortality are nonetheless feral in their passions. But fantasies, Knox suggests, are mirrors of reality, and do not exist without consequences. Doomed to night and shadow, her vampires offer the ominous prospect that progress is the true monster and remind us that daylight and illumination are very different things.

In Daylight, Elizabeth Knox has written a Northanger Abbey for the new century, an entertaining fiction that offers a potent summation and critique of a weary genre. Her style is meticulous and dreamlike, moving with a languor worthy of its nightwalkers. She demands and deserves a careful reading, because there is no doubt: Daylight is not just another vampire novel.’

Here are some answers I gave to questions from a student writing a paper on Daylight.

Are your vampires purely creatures of your imagination, or did you base them on someone or something else? I have read that Daylight was not your first foray into vampire fiction, so I assume you have had a fascination with them for some time. I am interested in whether you drew on inspiration from any other vampire sources? Some reviewers have, for instance, cited the works of Anne Rice. Do you see any parallels there?

Daylight was my take on Vampires—one of several I’ve come up with, but the one that best suited what I was trying to do in that book. Because I’ve played imaginary games for years (this is covered in my essays ‘Provenance’ and ‘Origins, Authority and Imaginary Games’ which are both in The Love School). I’ve been coming up with variations on vampire stories for years. The vampires in Daylight share much of what is essential in all vampire stories, and the metaphors implied in those story’s inventions—dependence on blood (addiction, starvation, parasitism, cannibalism, weird sexual congress); sensitivity to daylight (illness, seclusion, secrecy); and, most interesting to me, being long-lived. Vampires are history embodied, like the objects in museums, or holy relics. They are things surviving from past ages, not testimony – the history we find in documents—but evidence, things themselves.

In Daylight everything is connected beneath the ground. There are caves in the book, and other lines under the map, old paths like pilgrims trails or the Salt Route. In the historical sense the lines under the map are ideas and beliefs that have disappeared leaving mad traces. For instance, the Cathar idea of a good God and an evil God, a belief that the very old vampire Grazide still lives with. There are things that the vampire Ila does in the book that the contemporary characters have to deal with as mysterious or incoherent because they arise from poorly apprehended ideas he’s inherited from his maker, Grazide, who got them from a Christian sect wiped out by the Albigninian Crusade. The vampire Ila is whole periods of history contracted into a world view.

People cite Anne Rice at the drop of a vampire hat. Of course Anne Rice was first cited in connection with a book of mine with Vintner, which isn’t about vampires.

Did you feel any responsibility, or burden even, towards the vampire genre, given its considerable history? As a story Daylight still adheres to many of what I would describe as iconic vampire themes: immortality, blood lust, light aversion, and so on. Are these essential to making it a ‘vampire fiction’?

I don’t ever feel responsibility towards a genre, or works of the past. What a scary thought! Works of the past, if we know about them, are already looking after themselves. Douglas Winter, who wrote a lovely review of Daylight for the Washington Post, later said in an interview that Daylight was alive as a book in the (he thinks) stultified horror genre, because it was ‘written in defiance or ignorance of genre’. This is nice, and makes me into either a hero or a savant, but it isn’t true. To me—if I’m doing vampires, angels, golems, whatever, I just do it. (People are as puzzled by my ability to occupy ‘foreign’ territory. But I’m with Whitman on this: ‘I contain multitudes’. We only have a short term lease on the world, each of us, so, I say, let us imaginatively occupy anything we can imagine. Let’s use all the towels, muss the bed, and steal the soap! The problem for me is only ever how each book wants to be written. Vampires, angels, witches—these inventions are big enough to accommodate any imagination that wants to spend some time with them. I’m certainly never ‘in defiance’ of influence, and I’m too well-read to be ignorant—so I guess I just find that I metabolise what I love and am lucky always to feel my love as a communion, not a burden.

As to the last bit of your question—that is kind of an intellectual challenge. I’m sure it is possible to write a vampire story missing several or even all those elements. I’m sure people have done it. There’s Carmody Braque in Mahy’s The Changeover, for instance, sucking out poor Jacko’s life from within. And what about Gilbert Osmond in Henry James’s Portrait of a Lady, isn’t he a sort of vampire, a vitality and confidence thief, anyway.

Despite your evident respect for the tradition, your story is also quite original in its ‘take’ on vampirism. In particular you take the sexual theme as more central than the terror. Is Daylight a ‘love story’ and why did you deliberately set out to make your vampires sexy? Can you enlighten me about the inspiration behind your innovations in the genre?

Yes, Daylight is a love story. With Bad and Dawn, a pretty conventional love story, really. Ila and Daniel are another question altogether. They, too, have a love story. Daniel is in love with mystery—and starved of it, really. To Daniel, Ila is the mystery of history itself—Ila’s illuminated pictures, his appearance is Chambord’s Daylight, his story about the statue with the mark of inundation from other floods. Ila is the answer to the martyred nun Martine Raimondi’s desperate prayer in 1944. She prays for a miracle and gets a monster. What can God have been thinking? That’s what Daniel thinks. He’s is in love with all that. He’s in love with the turning moment. For instance the moment containing the butcher with the billhook on the path from the Castel Abelio to Dardo—how many times is that scene replayed in the novel, turning gradually to give up all its perspectives, including God’s. Daniel is far from God, and finds Him again because Ila is so sure God was watching him watch the butcher (who is watching the soldier, who is watching the grass snake on the steps.) Phew!

I think the vampires in Daylight are sexy and scary, and sexy because they’re scary (and meaningful). Except for Tom Hilxen, of course—he’s yucky—and when he siphons off Daniel’s blood in the chapel in Avignon, that’s very yuck (but sexy, right?) As for WHY my vampires are sexy—heavens!—I like to invent attractive characters, and I like to try to make readers fall in love with them. One of the things I love about narrative fiction—books/TV/film—is its power to make us fall in love with people who don’t exist. (David Thomson is very good on all this in his book about Hollywood, The Whole Equation.)

‘An ambiguously coded figure, a source of both erotic anxiety and corrupt desire, the literary vampire is one of the most powerful archetypes bequeathed to us from the imagination of the nineteenth century.’ That’s a quote from Nina Auerbach in Our Vampires Ourselves. Would you endorse this summary of the vampire as a literary genre—and why do you think this is— or do you disagree with her perspective?

Oh, I’m with Nina Auerbach on this one. Vampires are archetypes. That’s one reason I take fantasy seriously; because fantasy can deal more directly with archetypical figures than realism—even if it too often fails miserably to do so. (That’s no reason to stop writing it!)